Tomato yellow leaf curl virus has been a chronic threat to tomato production in South Georgia for more than a decade. The problem is only getting worse.

A University of Georgia researcher says eradicating the disease may not be possible. However, work continues to be done to help farmers select resistant varieties and manage their risks.

Severe cases of this virus have increased in recent years, especially in the fall when whitefly pressure is high. Tomato yellow curl virus, which is transmitted by whiteflies, can cause very high yield losses and reduce the crop’s marketability. In some cases, the entire crop can be lost.

“Right now, it’s really not uncommon to find infection rates over 90 percent in several fields,” said Rajagopalbabu Srinivasan, an entomologist at the Tifton campus of the University of Georgia College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences. “The ramifications of this virus could be huge if we don’t try to manage it.”

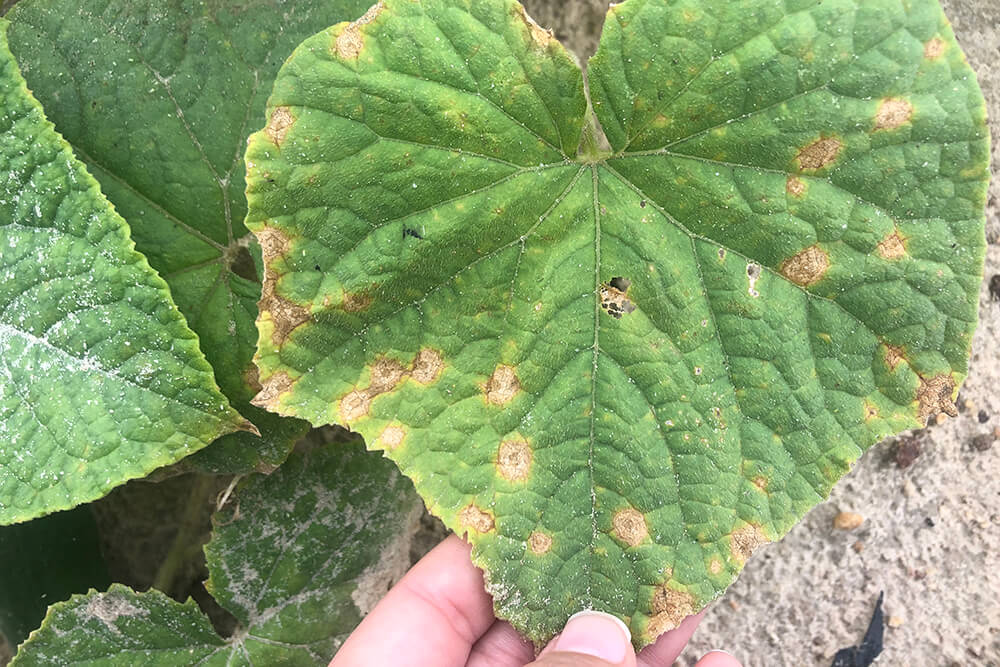

Symptoms of a tomato plant infected by the tomato yellow leaf curl virus include yellowing foliage, leaf curling and stunting. The virus had an extreme effect on tomato production last year, due in large part to heavy whitefly pressure. A year ago, plants started showing virus symptoms just two weeks after being planted.

The most common approach to managing the virus is to use insecticides. That tactic has proven to be futile time and again, though, according to Srinivasan. Insects with the virus can transmit it within five minutes of feeding, meaning a “super-efficient” chemical is needed to contain the spread of the virus.

In affected areas, farmers sprayed once a week last year and the virus still prevailed, he said.

“It kind of tells us that insecticides can be effective to suppress the insects but not the viruses that they transmit,” Srinivasan said. “In such scenarios, we’ll have to weigh our options and come up with some other tactics, which include resistant varieties and cultural tactics.”

Despite the availability of resistant cultivars, growers have been hesitant to use them. “(Farmers) believe that the resistant cultivars have poor horticultural attributes and often are not preferred by consumers. Growers have not actually resorted to planting these varieties because when these varieties came out, in the initial stages, they didn’t produce good tomatoes,” he said.

Srinivasan said farmers prefer susceptible varieties because they “produce really nice-looking tomatoes with good shelf life.” CAES researchers are currently evaluating new resistant varieties they believe will be good options for growers.

Another option that growers will have in the future is a risk-assessment website that Srinivasan hopes will be implemented within the next couple of years.

“This website will be developed with funding from the USDA-AFRI program. The growers can actually go into this website and plug in information to see how much risk they’re going to have if they plant with the options they currently have planned for,” Srinivasan said. “The website would also give growers options to minimize risks.”

Despite the virus’ persistence in South Georgia, Srinivasan and his fellow CAES entomologists David Riley and Stormy Sparks are confident that management will continue to improve.

“At this point, we’ve passed the elimination or eradication stage as the virus has already been here since the late 1990s. The options we have now are to manage this virus rather than eradicate it,” Srinivasan said.

.png)